We will have our limited range of locally-native ecosourced plants for sale beside the Strawberry Stand as and when possible from now until Xmas, but the roadside is often crowded, and/or too hot for the plants and myself, so if you would like to buy plants via email we can arrange to deliver them to the Eskdale Reserve roadside, or you can pick them up from our little nursery in Windy Ridge.

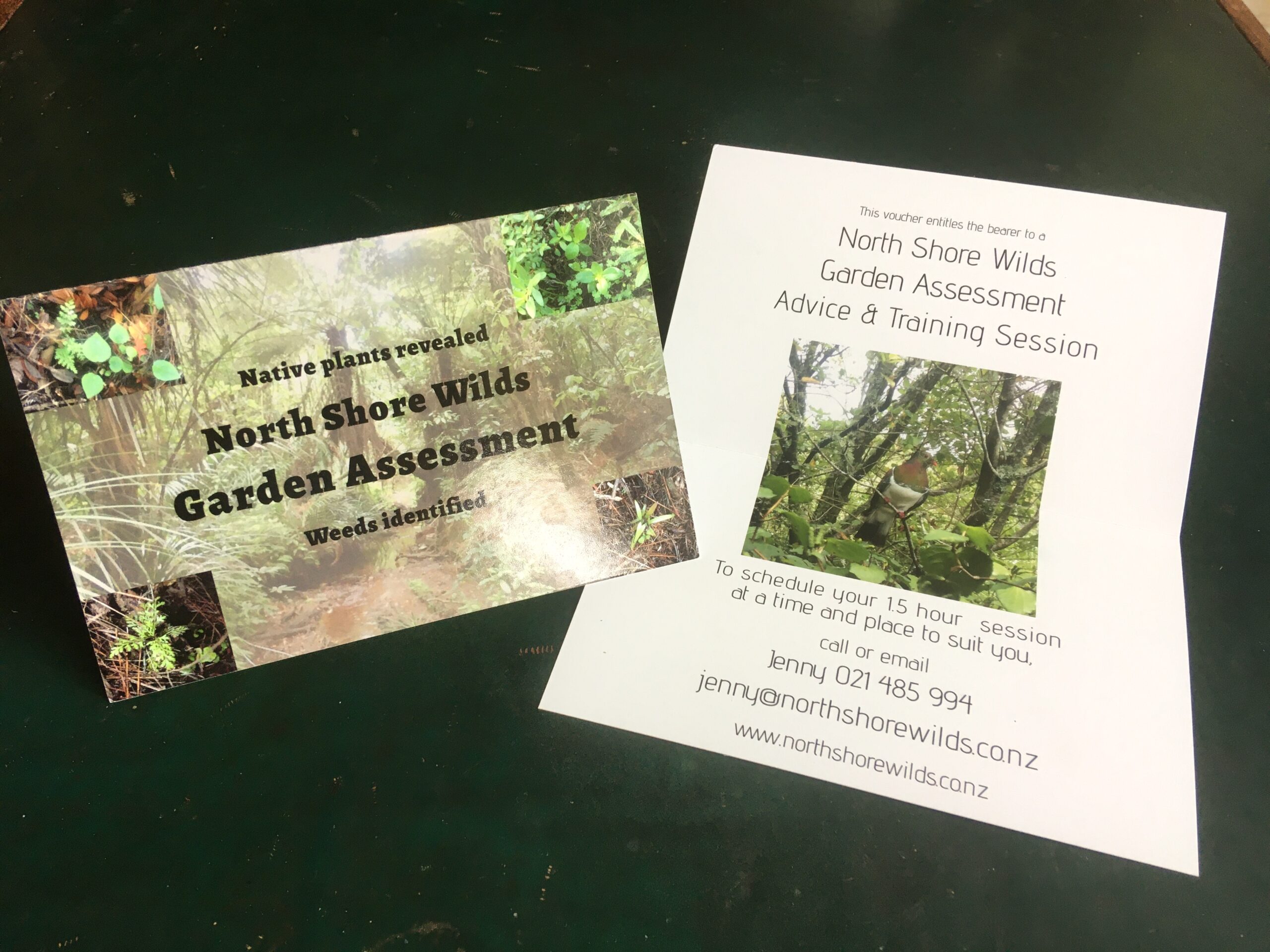

We also have for sale ten gift cards (with envelope), for our popular Garden Ecology Assessment by appointment at the recipient’s home, including plant identification and advice on chemical-free weed control for your property.

Plants available for immediate sale include:

Native sedges, or “grasses” as they are often referred to, popular in landscaping and ideal for absorbing heavy rain and preventing erosion, are hardy and self-maintaining.

Carex flagellifera from $3 each or 10 for $25…

….in 8cm pots for $5 each or 10 for $40 ….

Here are some of them lined up in front of Grandma and Grandpa, who are about 80cm high.

Carex flagellifera multiply both through division and by seed.

Kawakawa

We always suggest planting kawakawa in partial to full shade, keeping soil moist in summer, and buying a few to ensure having both a male and a female tree.

$5 each for 10cm pots…

8cm pots from $3 each or 4 for $10…

…or $10 each in 1-2L pots

Fuchsia procumbens / Scrambling Fuchsia – a pretty little creeper with tiny “ballerina” flowers to look out for in summer (but there are none on this young plant yet:) These Fuchsia plants are not ecosourced, but it is a locally native species)

This native species scrambles through undergrowth for up to several metres in sun or partial shade, and climbs to about a metre in places, but doesn’t get ouot of hand and dominate other plants. Our plants are grown by layering from this specimen (below) which has been growing beside this gatepost for about 20 years. Smaller shoots have climbed to about the same height – about 40cm – on the other side of the fence, but it has not spread more than a metre into the garden to the right.

We also have a few native trees , shrubs and ground covers of various kinds, including karaka, mapou, totara ti kouka, karamu, houpara and the tiny native sedge Carex inversa, which is good for filling cracks with its spreading rhizomes that help keep out the less attractive wildings such as dandelion, dock etc.

Contact us with orders or any queries.